Travelling the Eyre highway the thousands of kilometres to Perth brings to mind this country’s dependence on oil. Riding a bike or electric car from home to work and café in the inner city can give the impression that kicking the oil habit is a no brainer, but out here it’s a different story with the double trailer road trains carrying consumer goods to far away cities or diesel from the Port Bonython terminal to keep the huge machines of the mining industry going night and day every day of the year (as well as the massive tractors and harvesters of the cropping farmers doing Just In Time operations to match the fickle seasons). The real wealth of this country is extracted with oil, and the commuter and consumer economy depends on it just as much. On the highway the connection between the consumer economy and oil is more transparent, pulling up at the servo alongside powerful 4 wheel drives pulling off-road campers and caravans, let alone the houses on wheels, that so many of the grey nomads inhabit. If this was their only home it might not be so bad but in most cases there is a three or four bedroom family home under lock and key while they are on the road.

While the climate emergency will intensify the imperative to kick the habit of fossil fuelled transport and travel, part of the process by which we do so requires an acknowledgement of the power it has given us all directly and indirectly. As David recounted in Permaculture: Principles and Pathways Beyond Sustainability, his own realisation came in 1977 while out with a friend in a boat chasing seagulls on the Derwent River powered by twin 80hp outboard motors – more power than that wielded by ancient kings and yet not a thought for consequences. More recently his essay “Why I am not flying (much)” explained in some detail his reasons. In taking this long vehicle trip (about 13,600km not counting Bass Strait) powered by high octane petrol available on demand across this country for as little as $1.50 per litre and not much more than $2.00 out here on the Nullarbor is, in historical terms, an extravagance, and something our descendants if not our grandchildren will again regard as such. The 1,500 or so litres of fuel needed for the trip costs about the same as our fee for doing two Aussie St presentations and associated activity. Of course those speaking fees have to cover a lot of direct costs apart from fuel before there is anything for our time. Nevertheless, the idea that two speaking fees can pay for the fuel to move about 1.5 tonnes of vehicle, camper, bookstore, personal possession and food stocks (so we don’t have to eat junk and support Moles or Bullies) 13,600km over 4 months represents an incredible power density. How can fuel that powerful be so cheap? In terms of energy slaves that 1500 litres represents the hard labour of about 125 humans working an 8 hr day (ie pedalling a bicycle) every day of the trip without having to feed, clothe or house them.

More radical examples of kicking the oil habit while maintaining modest long distance mobility are documented in the Art of Free Travel and the actions of Charlie McGee, travelling minstrel in BEV (Biosphere Emergency Vehicle). Our approach has always been the make use the incredible convenience of fuel from the corporations, complete with its carbon footprint and blood spilt directly and indirectly to secure control of supplies, BUT to limit use and maximise value in the following ways:

- avoid commuting as a default way to work

- always multitask and backload on trips, whether short or long

- the longer the distance, the longer the stay

- slower is better (more fuel efficient) and see and learn more along the way

- balance pursuit of fuel efficiency with making best use of existing vehicles to minimise embodied energy costs in new manufacturing (and waste of discarded vehicles)

Of course it is easy to see the contradictions in our total boycott of Moles and Bullies (partly because of their war on farmers) while accepting fuel from oil companies and governments that have 500,000 dead Iraqi children in their fuel tanks (from the first gulf war alone).

Like our purchase of a few bullets (for ecological hunting) manufactured by companies profiting from the arms trade to war zones, we don’t have a really satisfactory answer to these conflicts between values and pragmatism. Obviously many decisions we all make involve trade offs. Being clear sighted about those trade offs and the real benefits and costs that we, others and nature pay for our decisions is the important foundation for any sustainable transition beyond what cannot be sustained.

While in Armidale Jock Coventry told me about growing up on the family grazing property, where his generation increased labour efficiency using motorbikes rather than horses to muster stock. Jock recounted enthusing the change to his uncle who acknowledged the gains but asked what had been lost. He pointed out that on the bike you have to look down at the terrain whereas on horseback, the horse navigates the terrain, allowing you to survey the country, learning from everything you see and hear in quiet and clean country air. Jock also noted the decline in the need for labour led to collapse of the on farm non-monetary economy as well withering of the local community including closure of rural schools.

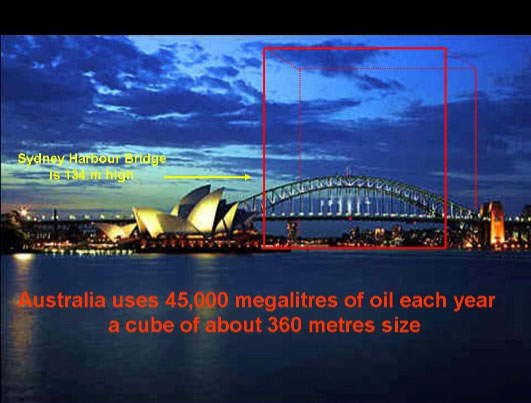

Full awareness of all we have gained and what has been lost by our use of fossil fuels has taken us most of our lives to come to terms with. Travelling the Eyre Highway renews and sharpens that awareness of the amount of oil that Australians consume each year even if it is difficult to visualise.

Graphic to visualise Australia’s consumption

Trackbacks/Pingbacks