Drought ravaged bushland on the New England tablelands

West across the tablelands the drought was taking its toll on native vegetation in a way we had never seen before. In places both shrubs and eucalypts had browned off leaves as if scorched by fuel reduction burning. The effect was worst in dense regrowth on shallow soils and least on large box trees in open grazing country where in parts there was bare dirt. Large mobs of stock were grazing the long paddock (wide road reserves and stock routes) and we even saw utes loaded with cut branches of Kurrajong heading for hungry stock.

Sheep grazing the long paddock on western slopes of the New England tablelands

Our first campsite was in tough granite country at the Copeton Dam on the Gwydir River. The dam was built in the 1970s to supply irrigation water for downstream cotton growers and was the last major dam built in NSW. It was holding less than 10% of full supply level. We avoided the campground facilities, crossed the massive wall and found a cut off section of old road in native pine/ box forest – nowhere in particular. We started collecting firewood and habitually trimmed up the Callitris pines to make a more fire safe and amenable camp. Leading on from this most rudimentary gardening David decided to give a nearby old Kurrajong a helping hand. The kurrajong is both a pioneer and long lived grandparent of a bird distributed, non-fire ecology than can build soil and form dry rainforests in the harshest country. Removing the dead wood from under the canopy, with consideration of likely fire sector dynamics but leaving the litter, compost and ground cover plants was the first careful intervention that lead on to felling three termite filled native pines that were struggling up into the Kurrajong canopy; wicks for the next bushfire to damage if not destroy this old tree. Just a bit of green gym with his half axe he bought in 1978, but also a small act of husbandry in a modern wilderness of uncared for land.

While thinning the dense crowded regrowth of native pines was once done on a large scale in inland NSW, other forms of long-term thinking are occupying the minds of engineers these days. At Copeton we saw a recently constructed spillway to augment the mechanical gates on the spillway built in the 1970s. We wondered if planning for climate change catastrophes and/or the super-wet years of 2010/11 had led to this urgent upgrading of infrastructure. The engineering vision that could design and build such a large spillway structure was awe inspiring (It was described as a “fuse plug” on the interpretive sign but what was not explained is that this structure of many thousands of tonnes was designed to blow out in the most severe imaginable flood flow to give maximum protection to the main wall.

The Copeton dam mechanical gate spillways now deemed inadequate to handle peak flood flows on the Gwydir River

While in Armidale we had been told about Mt Kaputar, a volcanic mountain from which they said it was possible, on a clear day, to see 10% of NSW. After a lunch stop on stilt roots of massive red gums on the banks of the Gwydir at Bingara, we took a terribly corrugated road into the Kaputar National Park which changed to a narrow and lumpy bitumen pavement that rose by progressive turns out of the box pine woodlands on harsh soils into grassy stringybark forests on the better volcanics and finally into a grassy manna gum/snow gum woodland on the plateau above 1300m that looked remarkably similar to the vegetation on volcanic soil around Daylesford (600m). A chilly night in the campground at Dawson Spring was our first paid campsite after which we checked out the slightly hazy but amazing views from the summit at 1580m, scrambled over the rock outcrops of the Governor, before headed down mountain to the plains.

View of the Mt Kaputar summit at dawn with Manna Gums showing the canopy form common in arid zone Mallee eucalypts, but here reflecting extreme exposure

After searching Narrabri in vain for organic food supplies we refuelled The Blue and drove out across the Namoi river plains (more cotton) to the settlement of Pilliga, which gave its name to the vast pine/box forests made famous by farmer/writer/historian Eric Rolls in his classic book A Million Wild Acres. But our campsite was in a desolate paddock with campers and mobile homes parked around the perimeter of the Pilliga hot bore baths, a modest public establishment that attracted the locals as well as the grey nomads, including us on this occasion. For Su this was definitely the best free camp yet. Luckily we had stopped by the roadside to collect some of the abundant wood, although at the bore, locals had kindly set up an honesty system with a barrowload of firewood plus kindling for those wanting a real campfire, but not so well prepared. While the forest was not too different to what we had seen recently, it did show signs of fresh green grass and annual weeds unlike all the country from the Hunter where winter rains had so far failed to materialise.

One of the many unused truck and other farm machinery converted to roadside billboards advertising local resistance to fracking for coal seam gas, a cause that has united conservative farmers and radical environmentalists

At Nevertire we passed a massive (at least in area if not megawatts) solar power station under construction by a beavering workforce of solar electricians, before continuing to Nyngan on the Bogan River (and yes there is a metal sculpture of “The Bogan” complete with rod and fish).

Our camp that night was out of town downstream under spreading Black Box trees. It was far enough back from the road to not notice the occasional night traffic but in the morning on the way back to town Su decided to stop and drag a kangaroo off the road that was a victim of the early morning traffic. Although her motivation was out of respect, the animal was a prime young female so we decided to harvest some meat. David quickly used his Leatherman to separate the hind legs complete with fur and stow them in the camper for the journey past another solar farm into the true outback beyond the agricultural land, where ironically we started to see more green and even water lying by the roadside. In parts the mobs of wild goats were browsing on the rocky landscapes, and apparently more traffic savvy than the hapless kangaroos (by the absence of casualties by the road side).

Wilcanna on the Darling was another iconic place, so different from the towns dominated by Big Ag that we had been through. In the absence of agriculture, the past grandeur of Wilcanna was mostly decayed but the revival of indigenous cultural awareness we had witnessed everywhere we travelled seemed to have taken over Wilcanna. Perhaps the successful resolution in 2015 of the 18-year legal struggle for Native Title rights of the Paakantji (River People) traditional owners was a factor in “reoccupation”

After trying a severely corrugated road out of town through fairly harsh country we abandoned looking for a free camp and returned to the caravan park where sprinklers distributed river water to maintain some green between the massive red gums.

David skinned and butchered the legs, hung the shanks for future stews and finely sliced the prime meat for flash frying. Although all fresh meat benefits from hanging for a day or three, we were confident such a prime animal would be good to cook the same day it was killed. Tender and excellent bounty of the land that the settler nation still fails to properly respect or value.

Kangaroo road kill cuisine.

Maybe it was appropriate that it was in Wilcannia a town where the good and not so good aspects of indigenous Australia, is out in the open, we savoured the good and chewed over the no so good aspects of settler relationship to the animal that has such a central role in indigenous culture.

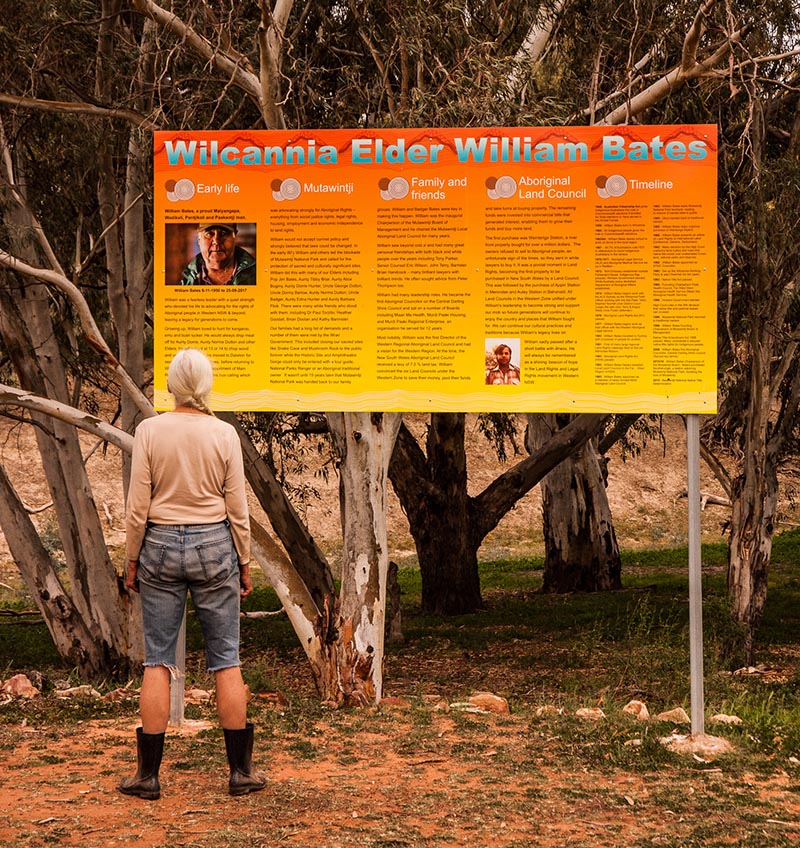

Su reading interpretive sign in Wilcannia telling the story of local leader in the fight for land rights, self determination and justice for his people.

We also spent a bit of time exploring the banks of Australia’s greatest “dryland river”, low in level and suffering from the ravages of overallocation (and straight theft) of irrigation water upstream, climate change driven drought and a cocktail of fertilizers and toxic chemicals that had the caravan park proprietor warning us not to go near the river water sprinklers. Despite its desperate condition the river is still a magnet for all, travellers and locals alike.

Dead pelican symbolising the state of the Darling River

Broken Hill was the next stop where the heritage and history is on display as the essential infrastructure of a tourist industry that now seems to rival the on-going mining industry. BHP has since divested itself of what is no longer considered “a world class asset” after nearly 150 years of mining. After exploring the townscape including sculptures by famous local Pro Hart, we headed out of town for a camp in the saltbush off a road to one of the open cut mines. Not the most quiet or salubrious campsite but a great place to climb the broken hills to see the sunrise, open cuts and the nearby town. Next we visited the amazing Pro Hart art gallery and museum, marvelling at the prodigious and diverse nature of his work, including one of his painted Rolls Royces.

Pro Hart sculpture dedicated to the ant like industrious co-operation of mining workers in their shared toil

Out of town 20 km on the Barrier Highway we found a lovely camp spot under the bulloaks in a dry creek bed near an old railway siding. A bicycle tourist from Colorado was also camped nearby and Su invited him to share our evening meal (more flash fried kangaroo leg, that had been marinated in lime and spices for a day after hanging for a day) For our guest who had experienced the carnage and stench of kangaroos on the road all the way from Perth, our meal together around the fire was a complete reset: “the best meal of his whole time in Australia”. In the morning our quiet self-powered camper was off before dawn heading east to make his schedule of 100 miles per day while we had our usual slow pack up to drive west into South Australia after campfire and hot breakfast.

Sunrise through the “bedroom” windows of the camper throwing light into “the kitchen”

While sacrificing a couple of citrus at the honesty bin to the quarantine gods of the SA agriculture department, we accepted a banana each from a Coffs Harbour bloke heading for Lake Eyre.

Back into agricultural landscapes the green of growing winter crops and annual pastures grazed by sheep was a shock to the senses after the dry of NSW and the arid zone. The grain growing country east of the southern Flinders seemed like a verdant paradise, but the signs of the bare baked soils of a killer summer and the rills and gutters of erosions revealed the green to be some sort of “green washing” covering the mostly unsustainable way our staple grains, the “staff of life” are grown before they are further bastardised by the milling, refining and baking processes that create industrial bread (and produce most of the gut problems our population suffers from). Not that I want to diminish the extraordinary job our winter grain belt farmers do in earning a mostly modest living working vast acreages with huge machines so we can satisfy our hunger and increase foreign exchange so we can buy wide screen TVs and four wheel drives.

While the spin about Australian agriculture feeding the world’s poor is mostly nonsense, it is true that wheat and other grains from our rain-fed winter grain growing regions in southern Australia does contribute to feeding millions in countries like Egypt that cannot grow enough grain to do so. And of course all permies can be getting the best quality food not grown at home, by buying products in bulk from the limited numbers of organic and biodynamic grain growers and millers who are a critically important part of building a parallel food system while boycotting Moles and Bullies.

Grain crops on the better soils (and rainfall) of Melrose with rainbow over the local grain silo

<< Previous Chapter — — — Next Chapter >>